It has been just over 100 years since the world last saw a pandemic and although we can rightly assume much is different in how the illness is battled, it is worth noting how similarly the world responded then and now.

With the First World War coming to an end, what became known as the Spanish Flu was on the move. In less than two years influenza killed more people worldwide than the war had in five.

The first known cases of this influenza were reported in the early months of 1918 in rear areas along the Western Front. It is unknown where it originated (one of four countries are likely scenarios) but since it was not covered by the press until it took hold in Spain, it gave rise to the name Spanish Flu. The first wave moved across the globe in the spring and summer of 1918, but it was the second wave that would prove to be far more deadly, and that wave took hold in Canada.

In September 1918 reports in eastern newspapers indicated that an epidemic of the flu was “raging” in Quebec where college students were getting sick and quarantines implemented. Deaths began to be reported amongst student populations as well as sailors who had become sick on ships in the harbor. Daily updates indicated the numbers of the sick and dying were growing as the illness spread to other provinces.

The first public mention of the disease in Saskatchewan was in the October 1, 1918 issue of the Regina Leader. Later that month cases began being reported throughout the province.

As the sick began filling hospitals the public health commissioner asked people to avoid crowds and not to sneeze or cough close to another person. All available nurses (even those who hadn’t yet graduated) were asked to report to his office so they could be dispatched to places where medical professionals were needed. He assured citizens there was no need to panic but that “everyone should eat nourishing food, spend time in fresh air, keep the house ventilated and avoid crowds” as reported by the Regina Leader on Thursday, October 18, 1918. Officials began searching trains coming from eastern Canada to look for signs of the flu among passengers. Anyone showing symptoms would be removed while those remaining onboard were encouraged to sit apart from each other and wear masks.

The October 24, 1918 issue of the Moose Jaw Herald featured headlines that demonstrated how grim the situation had become: “Deaths So Many, Graves Can’t Be Dug for Bodies”; and “City Will Provide Home for Children Whose Parents Are Too Ill To Give Them Care”. Hospitals did not have the capacity to keep up so hotels, barracks and schools were set up to handle the overflow.

Some occupations seemed to be hit especially hard. A request was made to use the phone “for business only” since telephone operators were becoming ill and those on the job couldn’t keep up with call volume. Those in the funeral business were stretched and appeals were put out to find more men to dig graves. It was difficult to get death certificates for the deceased because there weren’t enough physicians available to fill them out.

As the numbers kept climbing there was concern the situation was even more dire than what was being reported. The Medical Health Officer indicated he was worried there was a great number of unreported cases in private homes so the Lieutenant Governor issued a proclamation stating people should call on their neighbors, check in, offer help and report any cases of influenza.

The situation was province-wide and Outlook and area certainly wasn’t exempt from the pain brought on by the pandemic. Time spent looking through the pages of The Outlook from 1918 found glimpses of the heartbreak residents experienced and what they were asked to do to combat the disease.

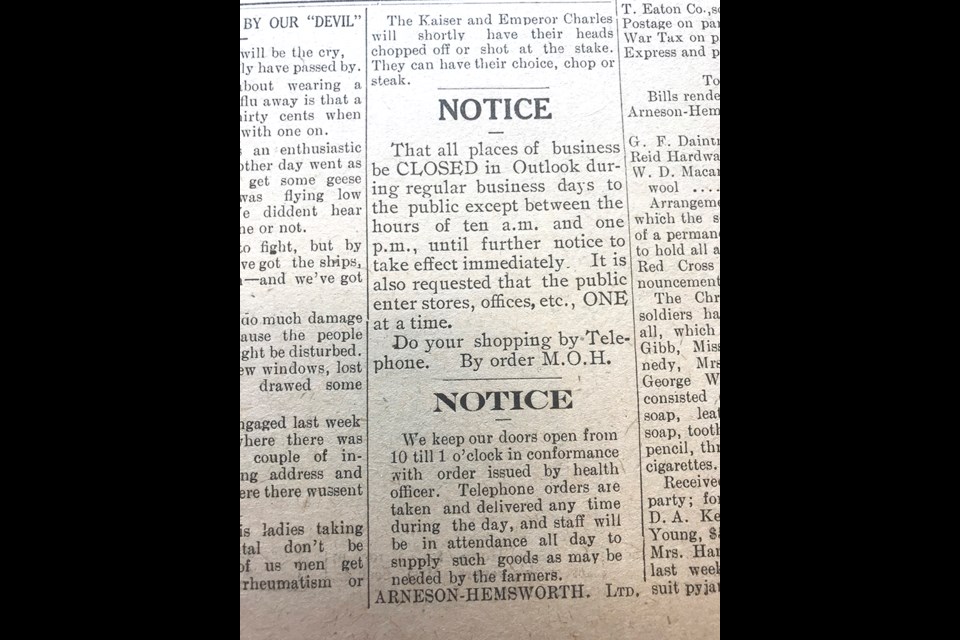

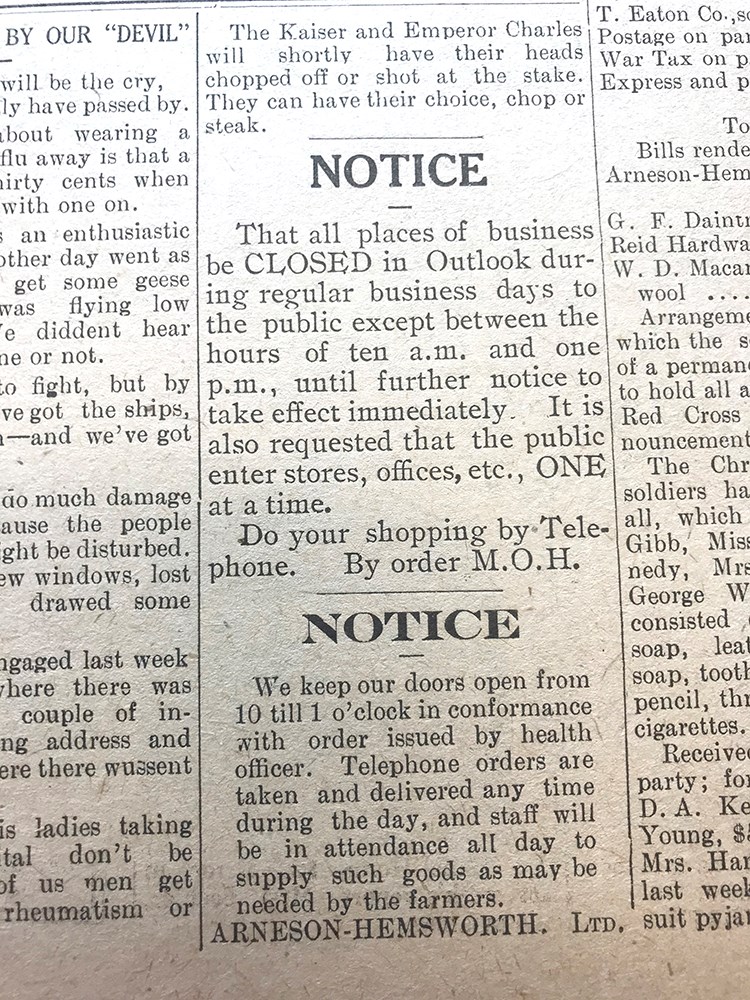

On October 24, 1918 The Outlook reported that following a special meeting of the council and Ministry of Health, it was decided that churches, the theatre and school would be closed temporarily. Cases had been reported in Outlook and in the Broderick district so local officials placed a ban on public meetings.

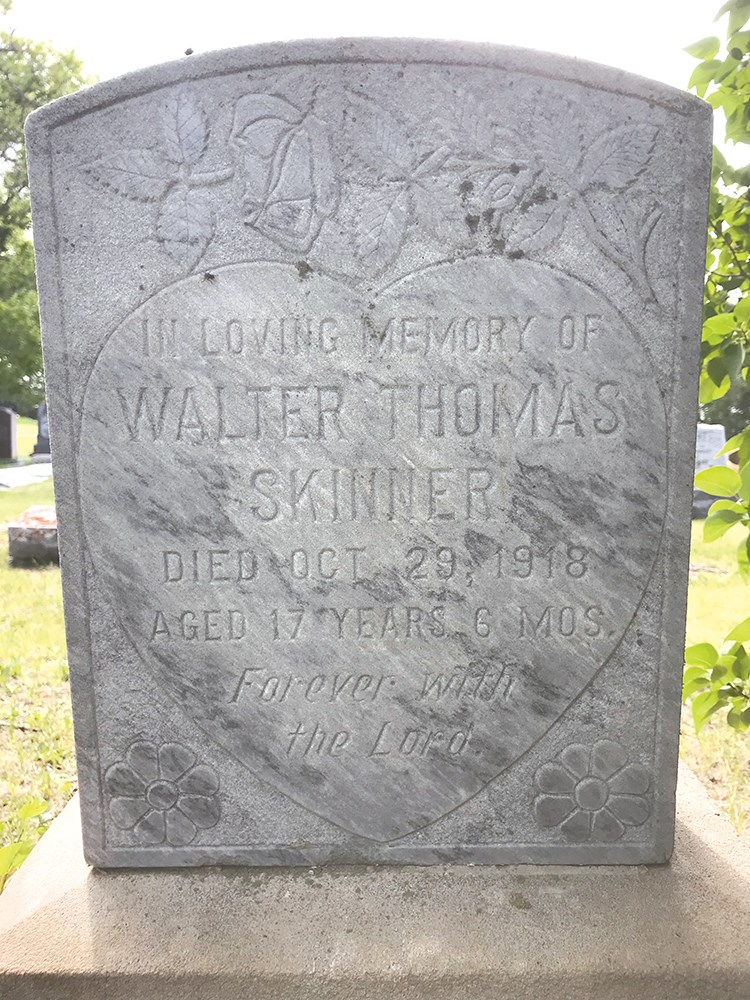

Reports from Macrorie, Ardath, Loreburn, Conquest and Glenside in “Local Happenings” named residents who had become ill, those who were recovering, and sadly those who passed away. In some cases members of the same family were lost within days of each other. Others found it necessary to travel to other places to care for loved ones. An Outlook man had returned from Nebraska “where he was called on account of the illness of his father.” An express messenger with the CPR was “called to his home at Willow Bunch last week on account of the death of his brother from influenza.” The next paragraph contained news of the death of a 18-month old child in Glenside from the terrible flu. A recent widow in the area died of the flu just months after her husband was killed in France while serving with the 128th Battalion. Ardath was reporting their good fortune in having had only one case thus far and the individual was recovering well. The very next week they reported the death of a 17-year old boy after a short illness “owing to the nature of the disease.”

The toll on caregivers mounted. A man in Hawarden was reported “dangerously ill” and those taking care of him were said to be “fairly played out.” A request was made for others to go and lend a hand. Doctors and nurses were becoming ill with the flu while others were said to be suffering from exhaustion. Some men in the area showed “their humane spirit by taking their turn at night relieving the nurses by waiting on the sick and doing any other work required of them.”

Group gatherings went ahead despite the warnings. At a wedding north of Outlook “nearly every guest contracted influenza from one who was present and appeared to be troubled” with illness. There were about sixty people present and nearly every family developed the illness, though none were reported as serious.

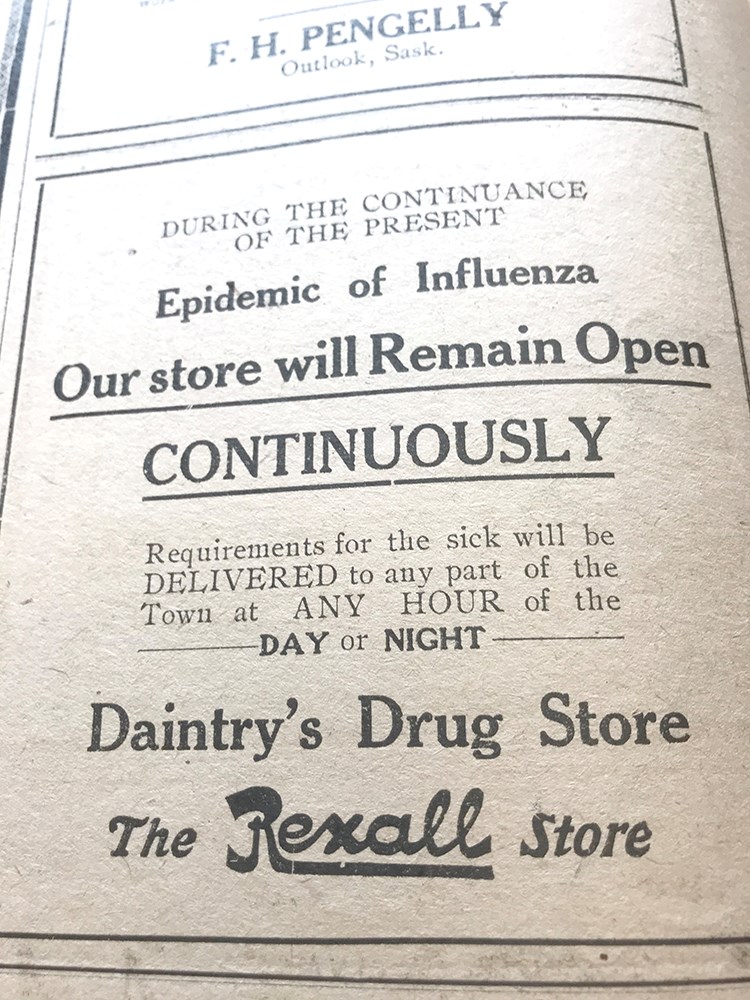

The Post Office was closed so people would not congregate in the lobby. Residents were encouraged to do their shopping by phone since businesses in Outlook were to be closed except for three hours each day. Communities like Loreburn ordered the complete closure of all stores. By the end of October the Macrorie sch to sell tickets to Conquest or Bounty since they were now closed to the traveling public.

It was cooperative efforts at the local level that came together to fight a global threat. Outlook College (known today as LCBI) offered the use of the boys’ dormitory as a hospital and the offer was graciously accepted by the town. The story went on to say, “Saturday the rooms were put in shape to receive patients and two qualified nurses engaged. A canvas was done of the town on Saturday morning for blankets and bed coverings and the ladies of the town responded liberally.” The college’s teachers volunteered to help out at the hospital, the Red Cross began sewing sheets, while the people of Broderick and district were noted for their kindness in providing provisions “with a free and lavish hand” to those working in the hospital. It was a pandemic felt by all communities and responded to by all communities.

Just weeks later the situation was described as “well in hand” thanks to authorities “having taken every measure to prevent the spreading and to stamp out the disease.” Masks were made and given away and people were advised to use them when in places of business since many were now serving customers again. However their use may not have been widespread according to the comment of one reader: “The trouble with wearing a mask is that a fellow feels like thirty cents when he’s the only guy with one on.”

Yet the steps taken seemed to have served the area well. It was reported that the success in overcoming the epidemic was due in great measure to the “untiring efforts of our medical men and the prompt action of the Outlook and Rudy councils in having the boys’ dormitory at the college transformed into a hospital which has been so ably managed by the nurses and volunteer help, all honor being due those who so nobly answered the call to care for the sick, showing a splendid spirit of humanity and one that will not soon be forgotten.”

By November 21, 1918 Outlook churches and the theatre could reopen and the ban on public gatherings was rescinded. It was expected that all patients would have recovered sufficiently in a matter of days so Outlook College made plans to reopen after Christmas. However despite all the optimism and positive signs, the “Local Happenings” column in the newspaper continued to report on those who were ill and confined to bed, reminding people that although the situation had improved greatly, the threat of the illness was still there. Further indication that the flu remained prevalent in the area is found in the history book of the Lutheran Collegiate Bible Institute in which President Gronlid indicated “the work of the Winter Term was badly broken up by the recurrence of the dreaded influenza.”

Precautions taken to mitigate the spread of the disease then and now remain much the same. What is also noteworthy in both is the admiration for health care workers. In November 1918 The Outlook reported that “the work done by the hospital staff is most gratifying and while several of the cases have been precarious, and in some very little hopes were entertained, all but one, a very severe pneumonia case, have recovered or are on a fair way to recovery.” The treatment and equipment available today versus 100 years ago take nothing away from the risk health care workers confront treating patients in 2020, just like the risks faced in 1918.

Worldwide, the influenza pandemic killed 20 million people. In Canada 50,000 lost their lives, with 5,000 of those from Saskatchewan. The town of Outlook fared well with just one reported Spanish Flu death in 1918, although other communities in the area saw greater loss of life. Numbers are difficult to assess given what was considered case under-reporting at the time.

Worldwide, as of June 22, 2020 the novel coronavirus has infected 9, 079, 527and killed 471, 278, with 8, 430 of those in Canada. Much about the pandemics a century apart may seem different; yet it is clear much is strikingly similar.

There was another item this writer came across in looking through the archives and examining the state of world at that time. It was a small piece, but one that deserves to be noted for its place in reporting right alongside the influenza pandemic. December 5, 1918; Tokyo - “Japanese newspapers are suggesting that Japan and China raise the race question at the forthcoming peace conference, with the object of seeking an agreement to the effect that in the future there shall be no further racial discrimination throughout the world.”

One hundred years later, and in the midst of another pandemic, the wish remains the same.